With its Citizens United and McCutcheon decisions, the U.S. Supreme Court clearly articulated the value of disclosure and transparency to the health of our democracy. After all, transparency is the best disinfectant, to paraphrase Justice Louis Brandeis’ famous quote.

Sadly, the type of transparency and disclosure envisioned by the justices doesn’t exist. Getting to the level that allows citizens to sleuth out actual “corruption”—the Supreme Court’s new test for regulating political speech—will take efforts and resources equal to deciphering the human genome.

Let me be clear, it can be done. In New York City, candidates and committees report their political donors, and every filing is audited for accuracy and compliance with regulations. The city pairs public contractor and vendor information with political donor information to reveal potential overlaps; auditors and lawyers investigate those possible conflicts. The city is in the midst of remaking its website, and soon all this information will available to the public.

So how do we get the rest of the country to a level of disclosure that the U.S. Supreme Court thinks is desirable?

Consider these realities:

The Federal Election Commission is finally upgrading its campaign-finance data and website, making information easily available via Application Programming Interfaces that let data flow seamlessly from one computer to another. This is a welcome improvement. Unfortunately, U.S. Senators still print their disclosure reports and send the paper documents to the Secretary of the Senate, who submits them to the FEC, which pays a contractor to type the information into a database. This archaic method is used by highly sophisticated campaigns that routinely apply advanced software to track and solicit donors. The cost of inputting this information has been estimated at more than $500,000 a year. That’s pure waste. Linking political donor data to contractor and vendor information, as well as other important government files and public policies—à la New York City—will likely happen when U.S. Senators begin sending electronic files directly to the FEC in a timely manner.

In the states, disclosure of donors by candidates, party committees, and ballot measure committees has improved in the past decade, largely due to electronic-filing requirements. Yet nearly half of the states still do not require meaningful disclosure of independent expenditures or electioneering communications. Perhaps more important, the lack of meaningful disclosure by lobbyists and their clients in more than half the states means the public has only a fleeting understanding of how these powerful influencers work. These are fertile grounds for corruption.

Reviews by the Center for Public Integrity of transparency and disclosure requirements in the states in 2015 and 2012—based on multiple criteria ranging from public access to information to legislative and executive oversight—found “secrecy, questionable ethics and conflicts of interest” were rampant. Forty-seven states received failing grades in CPI’s review.

At the federal, state and local levels, fragmented access to public information and lack of uniformity in what is required to be reported means the public has only the vaguest understanding of how influential interests are implementing public-policy agendas that often leave the taxpayer paying huge bills.

The U.S. Supreme Court, time and again, recognizes the importance of disclosure and transparency to the health of our democracy. That is heartening. That elected leaders at the federal, state, and local levels don’t prioritize elevating disclosure and transparency to high standards is extremely dismaying. And wasteful.

Corruption flourishes in the dark corners of our election and public-policy processes. If transparency is to be our disinfectant to corruption, we as a country have some hard work ahead of us. Our elected leaders need to either lead us into this new era, or get out of the way.

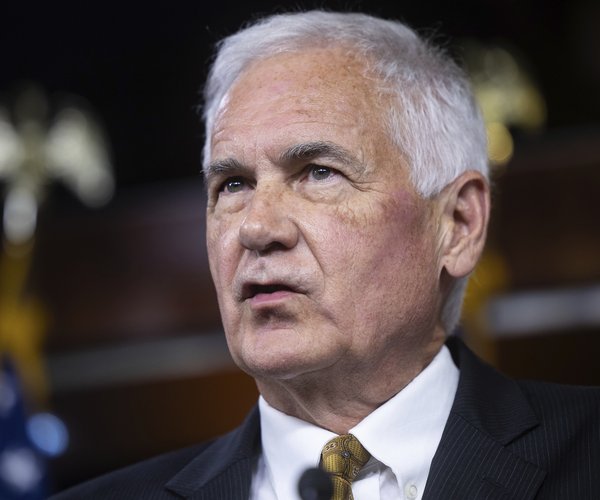

— Edwin Bender is the executive director of the National Institute on Money in State Politics (Follow TheMoney.org)